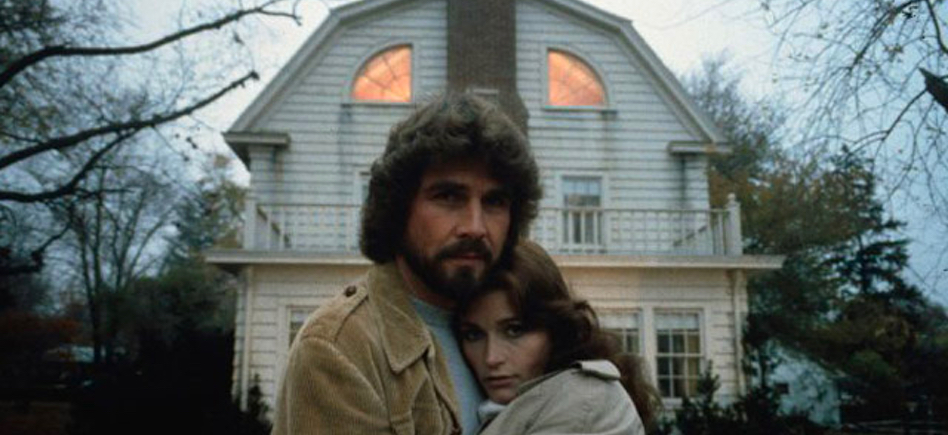

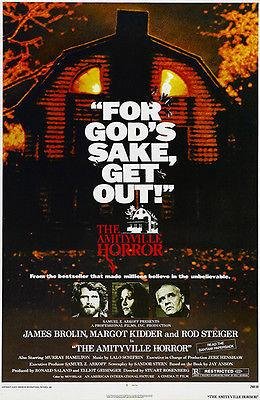

Often listed as a top picture in the horror genre, this 1979 release is rather dull and clunky. Based on a “true” story that is decidedly untrue, the Lutz’s (James Brolin and Margot Kidder) move into a cheap dream house in Long Island knowing full well a 20 year old murdered his entire family there the year before. When their local priest, Rod Steiger, comes to bless the house, the demons therein drive him out and eventually, blind him. The house soon possesses Brolin, and Kidder (and her three children) are endangered.

The house itself is awfully creepy and the score features a chilling sing-songy ghostly whisper of children’s voices. But Brolin is flat and ridiculously coiffed, even for 1979, Kidder is uninvolved, the children may as well have been mannequins, and Steiger overacts the hell out of his role.

Performances aside, the movie just isn’t that scary. Sure, flies congregate, the walls bleed, creepy eyes shine in the window, and there appears to be a guy dressed as the devil behind a wall in the basement, but these features come off about as frightening as a decently prepared house on Halloween. Director Stuart Rosenberg, who helmed some interesting films (Cool Hand Luke, The Drowning Pool) is clearly uncomfortable with the genre, and apart from some disturbing externals of the house, offers very little visually. It’s a blocky, uninteresting picture, and the ending (Brolin goes back for the dog!) is ridiculous, though not as ridiculous as when locals tell Brolin he is the spitting image of the 20 year old killer.

No 20 year old killer looks like this: