This is not a film review, but some events require a detour from standard operating procedure.

A close friend and fellow film buff sent me the following:

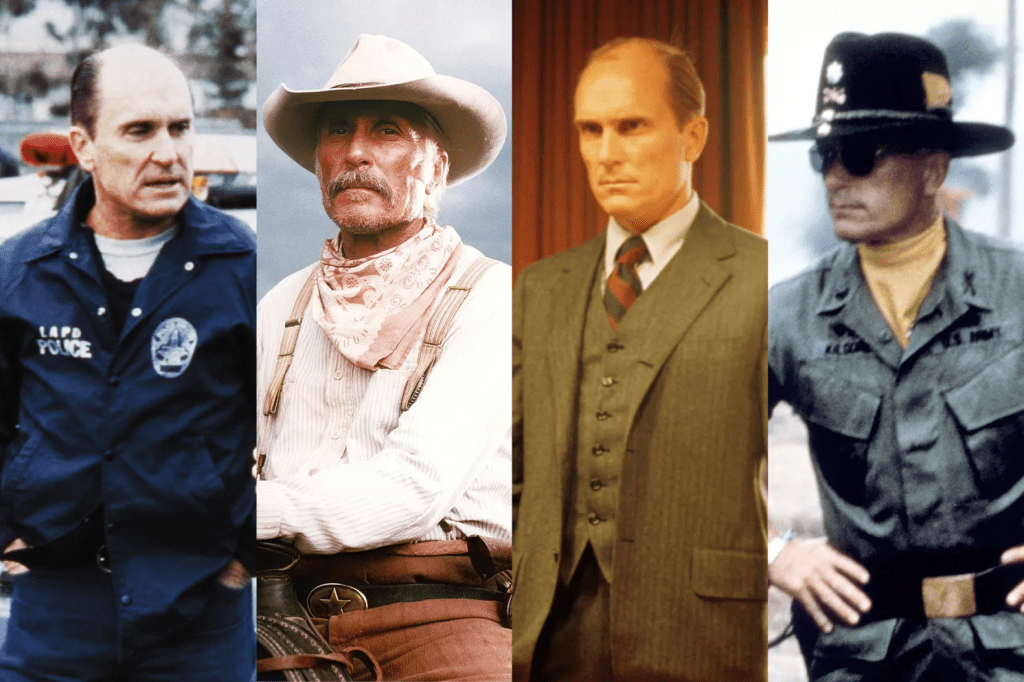

Robert Duvall’s very first film is hard to find and may not exist: a made for TV Playhouse 90, John Brown’s Raid, directed by Sidney Lumet starring James Mason as John Brown, filmed on location at Harper’s Ferry. In addition to Mason and Duvall, the movie had James Broderick and Ossie Davis. His second film and first feature was, of course, To Kill a Mockingbird. He made about 7 feature films in the 60s–mostly episodic TV. But those 7 features arguably set up the next decade of his career: Countdown, a failed film by Robert Altman, The Rain People, a failed film by Francis Ford Coppola, and then The Chase (Arthur Penn), True Grit and Bullitt (Peter Yates). Oh, yeah, he plays a gay biker and Richard Jaeckel’s lover in Nightmare in the Sun. So the 70s opened and he plays a lot of assholes: MASH, Network, Killer Elite, Great Northfield Minnesota Raid. Also a lot of fairly colorless people: I’m sorry, but Tom Hagen is a thankless role, and while he’s an interesting Doctor Watson, it’s not very showy. And a Good Nazi, kind of, in The Eagle Has Landed. Also a lot of movies we’ve forgotten about. But almost all of his movies share two characteristics: he’s getting much bigger parts and most are directed by or written by big names. So even though at the end of the 70s, the average person hadn’t heard of him, he’s got a lot of respect in the industry and criticis love his ass. Setting up The Great Santini, Apocalypse Now, True Confessions and Tender Mercies–and that’s a sequence of films that’s got few rivals, particularly given he’s starring in three of them. Now he’s kind of found his groove as a movie star–of this group, only True Confessions wasn’t Oscar nominated. Ironically, his 80s after that is a bit tame–probably taking some time off. And then the epic Lonesome Dove, where he creates Augustus, leading to his strongest decade not in movies (that’s the 70s by far) but in Robert Duvall Roles. He made 24 movies in the 70s, 12 in the 80s, and 23 in the 90s. He still worked up into his own 90s, getting another nomination and directing up into his 80s. From CNN, “…the family encourages those who wish to honor his memory to do so in a way that reflects the life he lived by watching a great film, telling a good story around a table with friends, or taking a drive in the countryside to appreciate the world’s beauty.” He was apparently a Republican, too. Long time buddies with Gene Hackman and Dustin Hoffman. I’m glad he had a better end than Hackman.

There is very little with which to disagree there, except for her misstep on Tom Hagen. Duvall’s turn as the “almost brother” is an understated, canny performance, pitch perfect to his co-stars, with quiet moments of real hurt. When Michael says, “You’re out, Tom,” Duvall shows piercing vulnerability, beseeching Vito with his eyes. When Michael attacks Tom for disloyalty, again, his bewilderment belies a greater fear (“Why do you hurt me, Michael? I’ve always been loyal to you”).

The scenes must be juxtaposed with Tom’s fights with Sonny, who also derided Tom, but with whom Tom was at ease, because for all his faults, Sonny was human, they were blood even if Sonny could cruelly suggests otherwise. And Sonny was dumber than Tom, a reality so patently obvious to Tom that his worth was never in doubt. They’d fight, Tom took it with a grain, and Sonny immediately apologized.

Michael, however, was inhuman and smarter.

The performance is masterful, like so much of what Duvall did.

Last thought. A Civil Action is an underrated legal thriller about a class action case brought against local polluters. John Travolta is the engine, a plaintiff’s lawyer fighting a massive, all-enveloping case and his own sense of inadequacy, and he is quite good. Duvall represents one of two corporate defendants, a wily, eccentric old line senior partner with a white shoe Boston firm. I’ve been around lawyers of all stripes my whole life. He is spot-on, brilliant, and inhabits the quirky-but-wise character entirely: