Andrew Dominik’s The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford is one of the best films of the last 25 years and would rank in my own top 25 of all time. So, no matter the negative notices, any of his pictures merits a look.

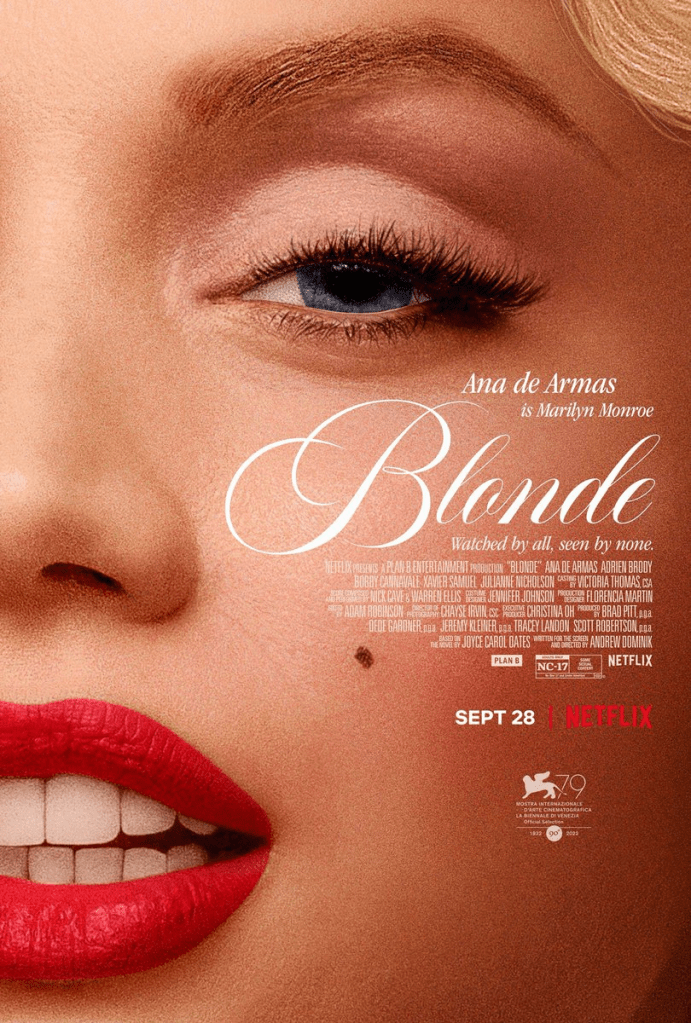

Blonde received scads of poor notices. Justifiably so.

The picture has much in common with Elvis, and you get the sense that Dominik, like Baz Luhrmann, was behind the eight-ball from the outset. Both biopics are devoted to broad pop icons with fixed public personas that, when pierced, reveal soft, dull goo. So, the directors make up for the deficit by untethering the stories from fact, gussying up the visuals, and stretching for a larger point. As with Elvis, we quickly learn a good-looking picture can only get you so far.

Make no mistake. Blonde is a visual feast. But it has no real narrative. We meet poor Norma Jean as a child brutalized by her mentally ill mother, and then she’s brutalized via casting couch, and then she seeks shelter in a “throuple” with two men, who take advantage of her sexually and financially. Soon, Joe DiMaggio (Bobby Cannavale) shows up out of nowhere, and then Arthur Miller (Adrien Brody), and then JFK, and soon, drugs and death. One calamity after another, one torment replacing another. None of her relationships are developed. Rather, her romantic entanglements just appear, are thunderstruck, and then we move to the next victim/victimizer.

It is all very sad, but watching a film is transactional, and you soon wonder, “Why am I supposed to care?”

Ana de Armas as Marilyn is occasionally effective (in particular, during a riveting audition), but for the most part, she’s a cartoon, cooing “Daddy” (to her own, unknown father and every man she has chosen to replace him) in a breathy, childlike manner at such a rate that you can almost see DiMaggio and Miller thinking, “Yikes! I thought the ditzy bombshell thing was an act? How do I get myself out of this?”

de Armas was nominated for best actress, and much like Natalie Portman in Jackie, the rendition is an over-the-top caricature of a public figure, where their peculiar tics are amplified. When her Cuban accent makes one of many appearances, it doesn’t really bother. There’s just too much else wrong with the performance, as if someone told de Armas to play Marilyn as a perpetual thirteen year old girl. With a concussion.

Not that de Armas was given much to work with. In one scene, she is with the none-too-impressed DiMaggio women, who are making spaghetti, and she lilts, “ooooh … real spaghetti? Like . . . not from a store?”

There’s plenty more where that came from in this ridiculous script. At the premiere of her first big film, as the crowd erupts in thunderous applause for the town’s new star, Marilyn breathily says, out loud, “For this, I killed my baby.”

Hoo boy.

Dominik’s missteps can also be traced to his misunderstanding of Monroe in the American consciousness: “If you spent 70 years enjoying a fantasy of a person; then a movie comes along that says she was not complicit in your enjoyment, it puts you in an uncomfortable position for having enjoyed it. People don’t want to be put in that position; they want her to be the one that created their enjoyment, and was along for the ride, then had a bad year and killed herself. That’s not the way it works. There’s no redemption in suicide. Americans don’t like you to monkey with their mitts too much. They very often want to jump to the solution without looking at any of the trauma.”

I am not unreceptive to some of these observations, but as applied to Monroe, Dominik is just wrong, He is talking about the Monroe of Elton John’s “Candle in the Wind” which was so long ago (1973, only 11 years after Monroe’s death) the song has been repurposed for Lady Diana (and will eventually be repurposed again when the next pop starlet dies before her time). Americans are not so protective of Monroe that Dominik’s pedestal tipping would elicit a reflexive defense. Rather, in modern memory, she was a sexy, mentally disturbed, marginal actress who sang a sultry “Happy Birthday, Mr. President!” publicly and privately and then overdosed. Side note: has anyone been taken down further in filmic history than JFK? When I grew up, he was the cool, collected president who saved his mates in PT 109 and stared down the Russians in The Missiles of October. Recently, in The Crown, he was a pill-popping whirling dervish. Here, he’s a #MeToo emblem, forcefully cajoling Monroe to perform oral sex on him in what has to be the worst scene in the picture.

I suspect Dominik knows the film fails, but credit him for a stout defense: ”Blonde is a very well worked-out film. Those who don’t think that aren’t watching it. If you sit back and trust that the movie knows what it’s doing, it’ll work.”

It does not. But if you are hot for a visually impressive, near 3-hour movie about a glamorous, vapid punching bag, Blonde is streaming on Netflix.