Howard Hawks’ western is competent, light, entertaining, and currently on MAX. The film also sports a few surprises, the most enjoyable of which is the performance of Dean Martin as the shaky alcoholic deputy trying to go cold turkey. It’s a hell of a dark and moving turn from a guy who you normally think is all easy-breezy, no heavy lifting.

Other notes.

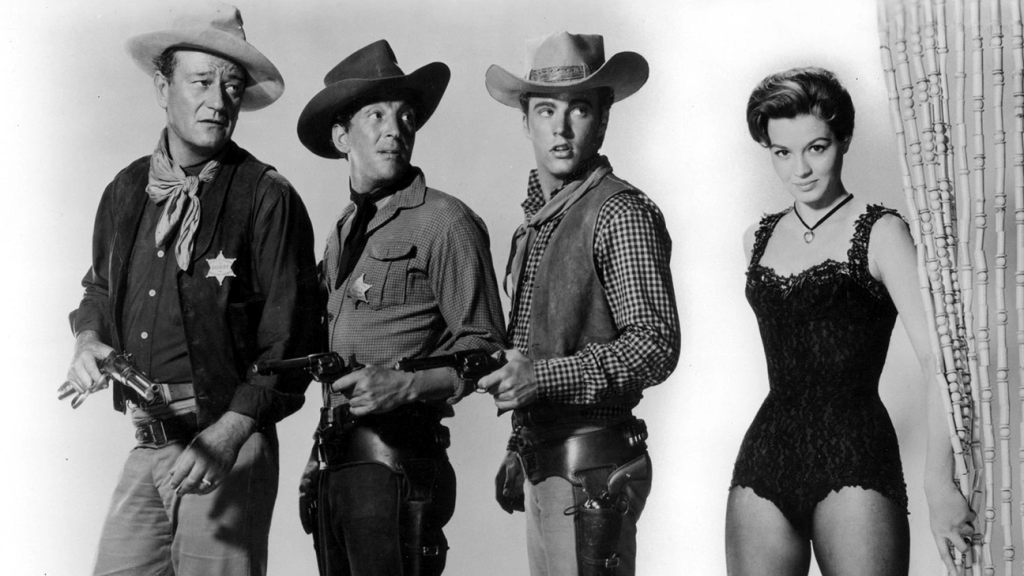

1) If you have Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson in a movie, they’re going to sing, and while it’s a little bit clunky when they do, the tunes are still a lot of fun. It would’ve been better if they just had Nelson playing guitar and Martin and Nelson singing together in the live shoot, but I presume the sound obstacles were too great, so they used a studio track and lip-synched instead. The dissonance between the music and the normal soundtrack is dramatic, but I imagine audiences in 1959 didn’t give two hoots.

2) I laud Martin’s performance, but Nelson is pretty damn good too as a youthful medium cool gun hand. He’s not asked to do much, but what tasks are given, he fulfills well.

3) Wayne made the picture in part as a rebuttal to the more cynical High Noon. Per Wayne, “A whole city of people that have come across the plains and suffered all kinds of hardships are suddenly afraid to help out a sheriff because three men are coming into the town that are tough. I don’t think that ever happens in the United States.”

4) Other than The Quiet Man, this is the only film I can remember where John Wayne is a romantic lead. It half works. Wayne smartly plays flummoxed, and Angie Dickinson’s magnetic performance nearly carries the day (when she kisses Wayne the first time, and he is stunned, they kiss again, and she says to him, “it’s even better when two people do it”). Romance works a little better in The Quiet Man, because Wayne was not asked to woo Maureen O’Hara so much tame her, an endeavor that seemed a lot like breaking a colt.

5) If my recollection is correct, Kevin Spacey modeled his performance in L.A. Confidential on Martin’s here. You can see it.

6) Trigger warning. Back to Angie Dickinson – va va voom!