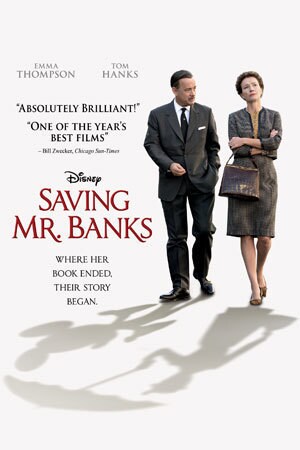

The writer of the Mary Poppins books, P.L. Travers, was apparently such a pain in the ass that, according to her grandchildren, she “died loving no one and with no one loving her.” As played by Emma Thompson, Travers more than fits this bill as she is whisked to Hollywood against her better instincts to be wooed by Walt Disney (Tom Hanks) in an effort to adapt her stories to the screen. Travers’ prickliness and exactitude with Disney and his team (Bradley Whitford, Jason Schwartzmann and B.J. Novak, all very good here) is the best part of the film. Unfortunately, director John Lee Hancock (The Blind Side) keeps interrupting the best part with flashbacks to Travers’ childhood, and in particular, her relationship with her whimsical, alcoholic father (Colin Farrell).

I understand the juxtaposition. The audience is supposed to learn what has embittered this awful woman. But you really don’t care (she’s such a witch that motivation is irrelevant), and you also begin to resent the interruption of the more interesting creation of a film.

Worse, the technique is cloying, leading to a sugary-sweet ending that has Disney melting the ice encasing Travers’ heart. In reality, Disney and Travers ended their relationship in acrimonious fashion, with Disney fed up with her stubborn nature, and Travers so offended she refused any further association between the company and her books. The disharmony is alluded to in the film, but it is near-blotted out by Travers’ copious tears as she undergoes a sort of catharsis at Grauman’s Chinese Theater.

Those were actually tears of fury. From Travers herself: “As chalk is to cheese, so is the film to the book. Tears ran down my cheeks because it was all so distorted. I was so shocked I felt that I would never write—let alone smile—again!”