When I saw the preview for Alexander Payne’s latest picture, I thought, “Okay. Older father figure. Private New England boys school. Some Christmas break bonding. Not the Baird school, but Barton. It’s Scent of a Woman, with a couple of tweaks.” I was right and also very wrong.

Now, I like Scent of a Woman. It’s occasionally moving, impressively manipulative, and entertaining as hell. Chris O’Donnell is vulnerable and empathetic. And even in a small part, a young Phillip Seymour Hoffman (poor George, “sitting in Big Daddy’s pocket”) resonates.

But the picture is near-obliterated by Al Pacino’s roar and Martin Brest’s complete lack of restraint. Hey, folks, not only are we going on a last hurrah with a blind depressive and his young charge, but let’s make the blind depressive a) do a flawless tango with a complete stranger; 2) have such a “fix-is-in” fight with his family that you feel for the bad guy, Bradley Whitford, the sneeriest of nephews; and 3) drive a race car in the Big Apple!

Hoo-ah!!!!!!

Still, like a Whopper Jr., the flick delights until the inevitable dyspepsia.

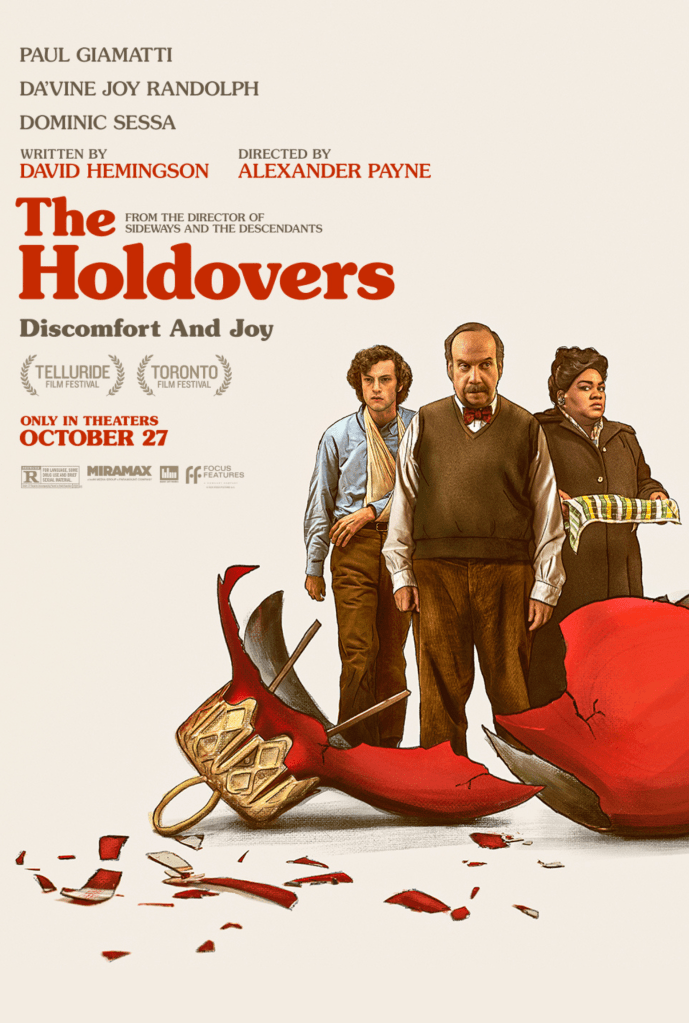

Now, the differences. First, without Pacino sucking up all the oxygen, The Holdovers has room not only for a Paul Giamatti as a strict, sneakily populist professor, and newcomer Dominic Sessa, the poor rich boy abandoned to staying over at school for the holidays under Giamatti’s thumb, but Da’Vine Joy Randolph, the school’s cook, who must endure the Christmas break and her own recent tragedy. I can’t commend her performance enough – restrained, clever, surprising, and then heartrending without a hint of stereotypical sass and easy schmaltz. Her sharing of the ins-and-outs of The Newlywed Game with Giamatti is primo.

But Pacino could not have allowed it. There was simply no space.

Second, Giamatti and Sessa actually grow, and bond, primarily through conversation, revealing a beautifully rendered mutually protective nature. Whereas, Pacino and poor O’Donnell simply pinged from situation to situation, each increasingly absurd, because they were confronted with two legitimate threats.

Third, again, whereas the scorching flames from Pacino’s engine disallowed any real growth, space or time for others, Payne depicts important interplay between or including secondary characters. The heartbreak and frustration of a bullied kid and his mitten choked me up, and after another poor holdover from Korea breaks from homesickness in the middle of the night and is comforted by Sessa, the job was nearly finished. Indeed, the kids in The Holdovers run the gamut – the dumb bully is there, but so too the clueless but tender-hearted jock and the poor youngsters. In Scent, with the exception of O’Donnell, every kid at Baird seemed to be some form of generic, shit heel carnivore or mere prey. Here, Payne delves a little deeper and produces some truly poignant moments.

Last, Pacino had one change to make, from bigger-than-life suicidal howler to a man who wants to live for himself and others. Conversely, Giamatti is seemingly a martinet, but in fact, turns out to be multi-layered. Rather than merely having Giamatti overcome his condescending and authoritarian nature, writer David Hemingson explores several aspects of his personality and past, all of which fill in the puzzle. And Sessa isn’t the only contributor to his growth, which fleshes him out even more fully,

The end of the film is a bit of a surrender to Scent’s need for big dramatic closure, and in particular, one Giamatti zinger is off-kilter and completely out of character. But the sin is venial.

If they are still holding the Academy Awards, I see a slew of nominations, and if you can get some juicy early odds on Da’Vine Joy Randolph for supporting actress, go heavy.