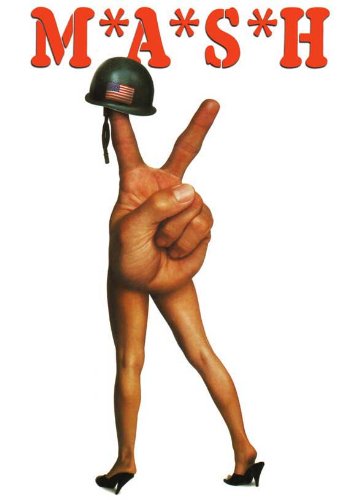

A technical advance in both sound and movement, and a caustic, first-of-its-kind black comedy, Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H was once deemed a masterpiece. Alas, now, it is as culturally atonal and offensive as Gone With the Wind.

The women in the film are nothing but sexual playthings, constantly subject to the predations of Trapper John, Hawkeye and all the rest of the misogynists who inhabit the camp. The nurses are first and foremost flesh to be pawed at, conquests to be made. Add an indelible strain of homophobia, a black character named “Spearchucker” and Trapper John and Hawkeye in Japan yukking it up with racist Charlie Chan imitations, and you end up with the transformation of what used to be an iconic, anti-establishment, anti-Vietnam (Korea just plays the part) film into a vessel for the most retrograde and debilitating of social views, a moral blight as offensive as blackface.

Mind you, I do not come to this conclusion lightly or happily. Before my own reeducation, I would have found this a clever, funny and brash film. The characters possess incredible medical gifts and live in an untenable situation, surrounded by gore and death, and they resort to sophomoric gags and easy sex because that’s what some people under stress do, especially in dark comedies. The old me would view this film as cruelly hilarious. I might have also found the treatment of the women tempered by their corresponding consent, agency and obvious value to the camp.

But that was before I understood the power of patriarchal constructs. My God, at one point, Hawkeye brings a female nurse to a depressed colleague as if she were a comfort girl to a marauding victor. And she is dreamily driven off, her lust was so sated.

The brutal ouster of the pious Frank Burns and the ritual humiliation of Hot Lips Hoolihan aren’t the mere comeuppance of villains. Watch again as she is unbared in the shower. The leering men settle a bet as to whether she is, in fact, a true blond; she writhes, naked, abused, on the shower floor while they hoot and holler and jeer. Despicable.

God help the campus movie house that accidentally runs this baby.