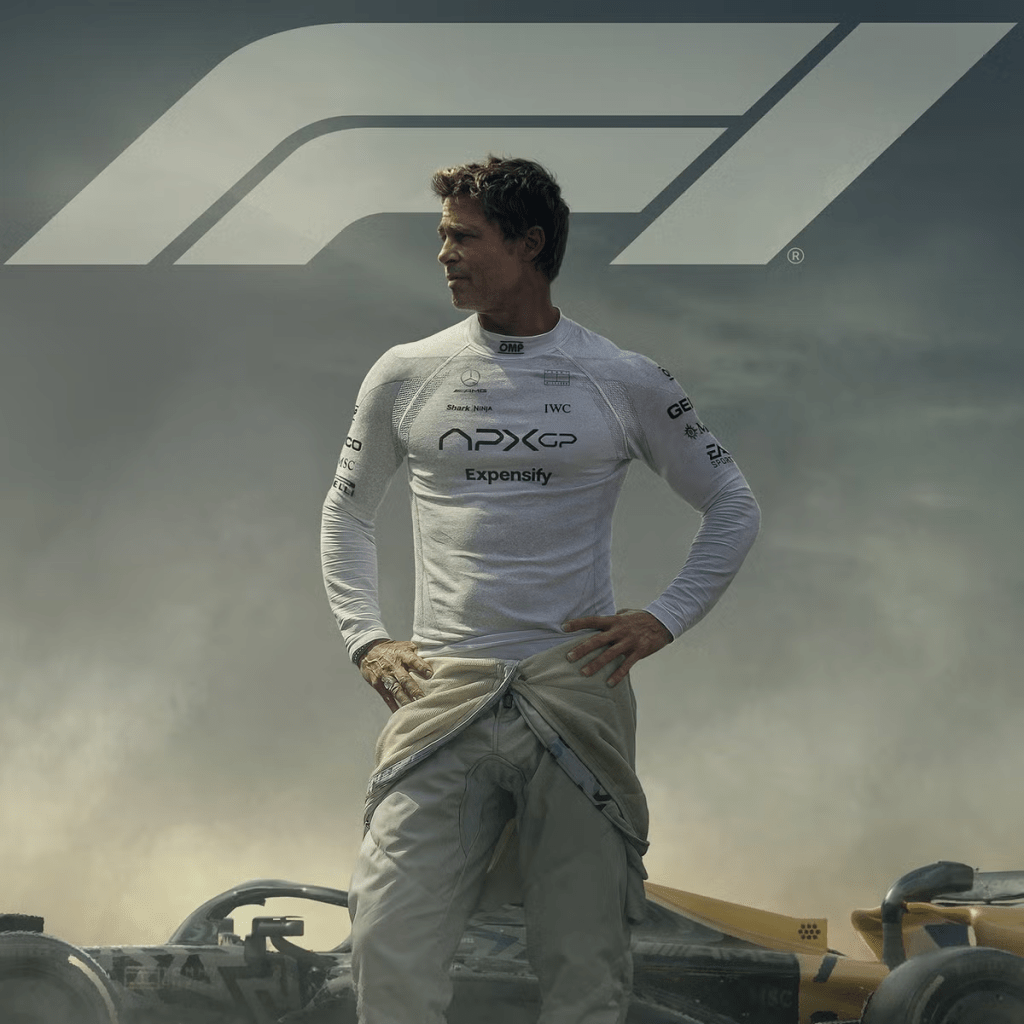

A big, flashy, visually overwhelming nirvana for speed junkies. But when cars are not going vroom vroom around the cinematic coliseums of the Formula 1 race tour, the film is unoriginal, dull, sexless, and stupid. It is also badly acted (Brad Pitt excepted, as he doesn’t act so much as pose).

Pitt is a journeyman racer, much like Tom Cruise’s Cole Trickle in Days of Thunder, though Cruise was silly as an old “I can race anything with wheels” hand given his youth in that picture. Pitt is more plausible as a man who can race anything, be it in NASCAR, Lemans, Formula One, Baja, or, the Sahara, on a camel. But he’s still silly as a a man looking for something transcendent and elusive, like Kwai Chang Caine in Kung Fu. When Pitt’s old chum Javier Bardem arrives to offer him a spot on his flailing Formula One team, Pitt can’t say no even if it interrupts his quest.

The old timer Pitt joins the team and runs into a hotshot younger driver teammate (Damson Idris). Idris is resistant to the grizzled interloper. He makes his mark on social media more than on the track.

Pitt teaches him maturity, discipline and self-respect.

Pitt also runs into team car design guru Kerry Condon.

Condon teaches Pitt how to be a good teammate.

They also sleep together.

Pitt has not had very good on-screen chemistry with women since Thelma and Louise. The trend continues Here, he is a stoic, and in return, Condon musters all the heat of a flagging sterno cup. With a strongly established “older brother, younger sister” vibe, they have what can only be envisioned as some of the worst sex in history.

Just when you are nodding off, another race will start. You will perk up, because the spectacle is kinetic and exciting. But you can only watch so much racing. These people will have to start talking again, and when they do, it is drivel.

The plot then begins to echo that of a much better racing film – Talladega Nights. There is corporate skullduggery in the form of Tobias Menzies, who wants control of the entire racing team and schemes to depose and supplant Bardem. Like Ricky Bobby, Pitt must not enter the final race for Menzies’ machinations to succeed.

Pitt, of course, enters the final race and saves the day.

In a withering coup de grace, Pitt texts Menzies an emoji.

It is the finger.

Now, we have just spent an entire film trying to establish that Pitt is a simple, grounded, live-in-your camper, shut-out all of the noise enigma.

Yet, in declaration of his own worth and independence, he texts an emoji.

Yeesh.

The movie is terrible when characters talk, impressive when wheels are turning, a bit of a conundrum, because I can’t imagine it would transfer as well at home.

Use your best judgment. Knowing what I know now, I believe mine would have been to forgo the film and watch the vastly superior Rush.