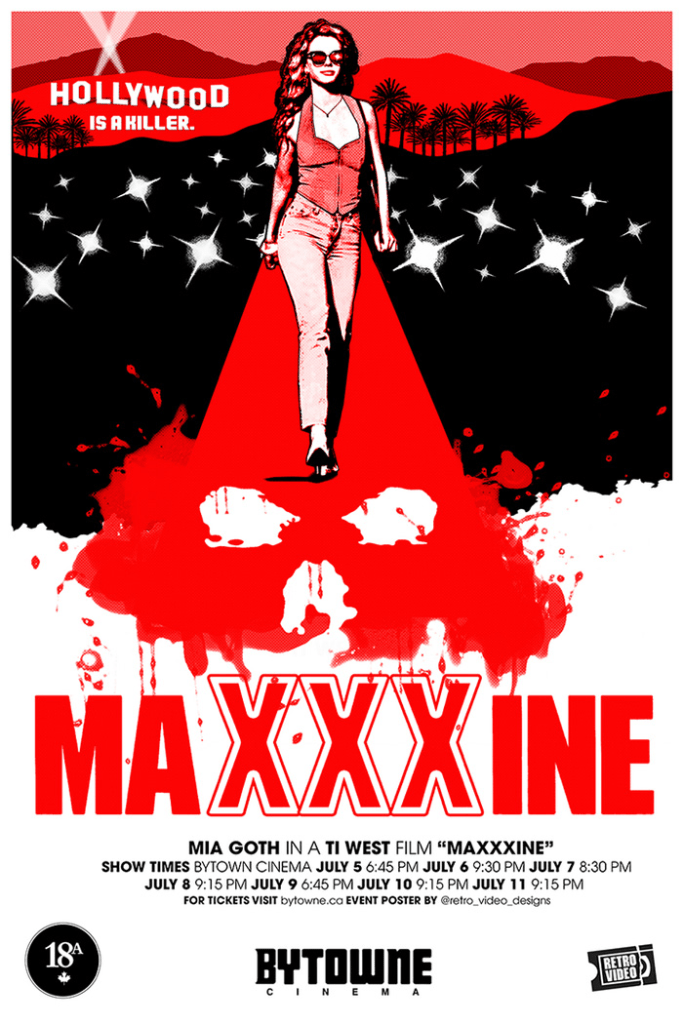

My dive into the crime films of Amazon Prime gets deeper.

I was intrigued by this flick because I like Jeff Bridges, the movie was an early Oliver Stone screenplay (a co-write), and it was one of last films directed by Hal Ashby (Shampoo, Being There, Coming Home).

I don’t have 8 million reasons to hate this film, but I have 8.

- Stone’s writing is garish and ridiculous. In an attempt at modern noir, we actually hear Bridges say, in voiceover, “Yeah, there are eight million stories in the naked city. Remember that old TV show? What we have in this town is eight million ways to die.” A high-priced call girl ups the retch factor, cooing to Bridges, “the streetlight makes my pussy hair glow in the dark. Cotton candy,” as she lays out ala’ Ms. March 1978. Maybe these gems were penned in the source novel by Lawrence Block. I don’t know. It doesn’t land here.

- Hal Ashby knows about as much about film action as I do taxidermy. It’s not like Coming Home’s Jon Voight was doing wheelies in his chair. This picture, which involves blackmail and cocaine and kidnapping and gunplay, is as flat and unimaginative as professional bowling.

- As the alcoholic ex-cop, Bridges seems as confused by the script as the viewer. There are times you feel, his eyes alone, Bridges is communicating, “What the hell is this thing about, again?” When he’s involved in a bad shooting, and guns down a man in front of his family, he says, “Shit.” Like when you don’t get a good score in Skee Ball. And then, “Fuck,” like when you leave home without your iPhone.

- Bridges is also forced to play an alcoholic who relapses; he does this by reprising his role in Thunderbolt & Lightfoot, after he was thunked on the head.

- The plot is inane. Bridges is lured into the entire mess because the girl with the cotton candy pubic hair heard his name from the friend of a friend.

- Roseanna Arquette is terribly miscast as the sultry, misunderstood, cynical call girl with a heart of gold. Arquette is cute best friend, quirky neighbor. She ain’t this.

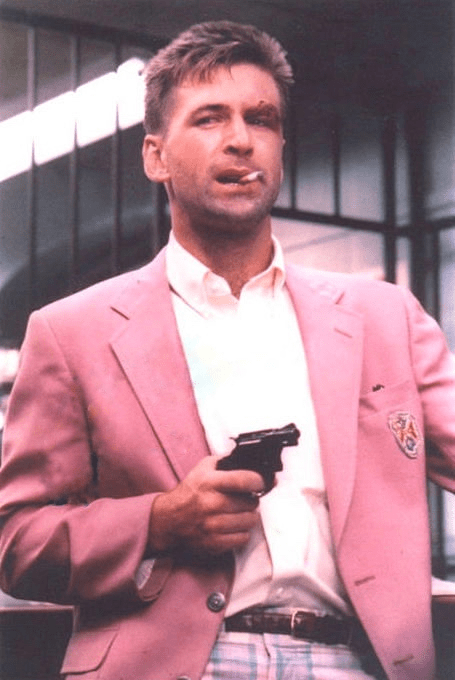

- The supporting turns are execrable. Andy Garcia is so over the top (see below), it’s hard to stop laughing, as if he saw Scarface and said, “Hmmmm. Pacino seems a bit muted.” Another actor, Randy Brooks, nemesis to Garcia, is also near-lunatic. Brooks scurried off to TV after this flick, only to return as the worst actor in Reservoir Dogs six years later. The cotton candy girl is the badly miscast Alexandra Paul. She is the girl next door. Here, she’s over-the-top coquettish, as erotic and worldly as Georgette in The Mary Tyler Moore show. To be fair, this may not all rest on the actors. From the analysis below, “Ashby’s style of directing, according to Block, involved letting the actors do takes where they exaggerated their emotions, before reining them back in for subsequent takes. Since Ashby did not have final cut, some of these ‘dialed up’ takes were used in the film.” Seems like all of them were.

- Scenes are interminable. The characters scream the same thing at each other ad nauseum or endlessly posture. Behold, the longest, loudest, most idiotic confrontation scene in film history:

Apparently, I am not alone in my derision and confusion.