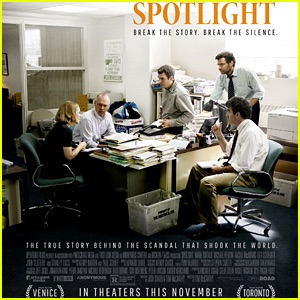

This is a gripping but measured film, a reportorial procedural and a meditation on the impact of the sexual abuse scandal that rocked the Catholic church in Boston, as reported on by The Boston Globe in 2002. “Spotlight” refers to an investigative team of the paper (Michael Keaton, Mark Ruffalo, Rachel McAdams, Brian d’Arcy James) who, under the direction of a new editor (Liev Schreiber) takes on the case. As they dig deeper, the breadth of the scandal widens (the number of culpable priests balloons from 13 to 87) and the institutional protections surrounding the church become more evident and intrusive. The story also takes its toll on the team, all some form of Catholic (cultural, lapsed, etc . . . ) at the time of the investigation.

The film is economical and direct and it stubbornly avoids cliche’ and histrionics. It is also a rare “based on true events” movie that feels authentic throughout, not jumped up or glamorized. It is very similar to A Civil Action, another Boston based movie that tackles a legal case (water contamination in Woburn) by analyzing the city and its institutions. Like that film, Spotlight packs its biggest punch during scenes of interviews with the survivors of abuse, which are nothing short of heartrending.

If you want a gripping movie about the mechanics of taking on a story like this, this is it, and if you want a companion piece that shows exactly how an individual molester operates, I recommend Doubt. Watching this film, as with Doubt, stirred my own memories on the subject, having been educated by the Catholic church for eight years of grade school and by the Jesuits for four years of high school. I saw the picture with my kids and tried to explain how what is now an indelible black mark on the church wasn’t exactly a deep, dark secret by the time I reached high school, yet somehow, was not a full-fledged scandal. I explained that we had a religion teacher who was very charismatic, but who you just kind of knew not to be around. Why? It’s hard to say. It could have been my own sense of it, or the fact that my brother or his friends imparted some decent advice, or the fact that after gym, when you were showering, he could sometimes inexplicably be seen in the locker room.

Whatever the impetus, you learned not be around Father Bradley, but I guess I just assumed that all boys shared the same sense of something being off and were similarly self-protective. That wasn’t the case, and in 2007, I was one of thousands of recipients of a mass email detailing the misdeeds of this priest at our high school, and at other places where he taught afterwards, encouraging us to report if in fact we had any knowledge of his abuse. Without the work of The Boston Globe on the story, that email may never have come to be. In that manner, this film is a testament to solid, door-knocking, pavement pounding reporting.

If you’re interested in the priest who plagued my school, the story is here. The original Boston Globe story can be found here.