I was hoping this touching film would be properly rewarded at Oscar time, but it was ignored. The omission is even more galling given the Academy’s decision to nominate 10 films this year, including the dreck of F1 and Frankenstein. Getting an Oscar nomination is never a confirmation of merit. But with 10 nominees? Please. Noah Baumbach’s story of mega Hollywood star Jay Kelly (George Clooney) in midlife crisis is clever, entertaining, and tender, and Clooney gives his best performance since The Descendants. The picture deserved better.

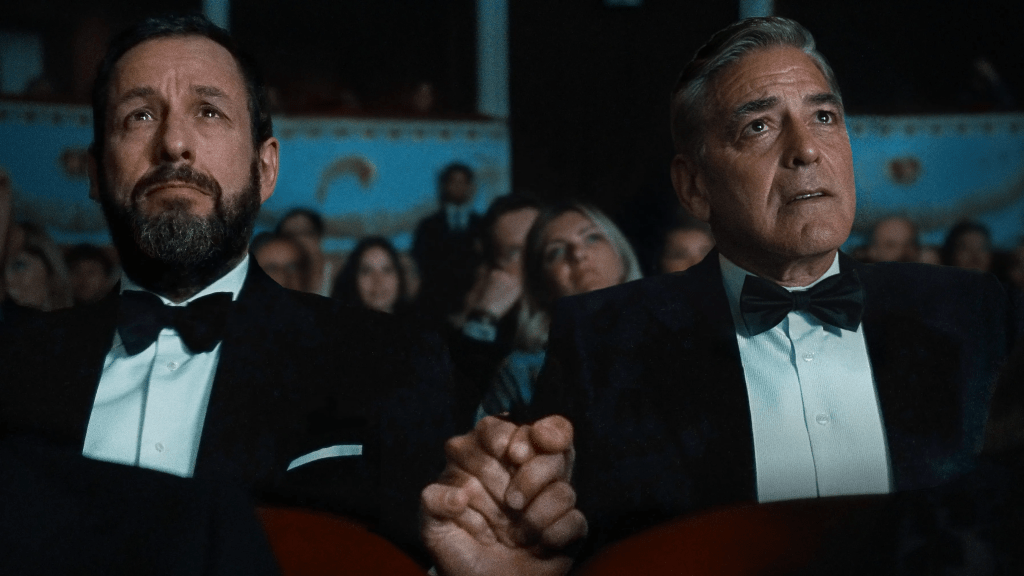

After the death of a mentor, the man who “discovered” him, Clooney is approached by an old friend from acting school (Billy Crudup). In the hope of establishing more of a real connection with both his past and normality, Kelly invites Crudup for drinks to reminisce about the old times. Unfortunately, Clooney is a massive, unknowing target, and he becomes the repository for Crudup’s bitter regret, as well as a TikTok sensation when the two get into a fist fight in the parking lot. Clooney, however, is not deterred, and takes his retinue, led by longtime manager Adam Sandler and publicist Laura Dern, to chase his younger daughter through France on his way to a tribute ceremony in Italy. To be unencumbered is a freeing experience for Clooney, albeit one that is laughably abnormal. He is recognized, fawned over, and catered to by a staff of five, and soon, even he sees the absurdity in his efforts.

The trek is infused with real heart and pathos, and throughout, Clooney flashes back to his ascent to stardom. While he seeks to reconcile himself to failures with family and friends, including his father (an irascible Stacy Keach) and an older adult daughter, who is estranged and embittered and attributes all of her mental torments to her wanting father, ultimately, they are not there for his moment. Clooney is left to the expected support from his longtime manager and assistants, but Sandler himself is going through his own crisis, realizing the limits of friendship in his uneven relationship as the fixer of all things for megastars. Dern has had it, and bolts with a “save yourself, this man does not love us” warning for Sandler. Eventually, Clooney is alone.

There are wonderful exchanges, poignant moments but, thankfully, no real resolution. Baumbach studiously avoids the pat. This type of film would normally result in some kind of oath, or commitment, or suggest a rapprochement, a teachable moment. Here, it ends with Clooney at the festival given in his honor to credit him for his life‘s work on the screen, and his lesson is not quite clear. Yes, like all men and women, Clooney has made mistakes, but when you get to see the joy in the faces of the people who love his work, work that has accompanied and maybe even inspired many of the moments in their own lives, there is at least a rebuttal to the regret.

For some, this, I suspect, may be too much sentimental log rolling for Hollywood. I ate it up with a spoon and wanted more.

A lovely film, one of the best of the year, replete with fantastic, unheralded performances. Sandler is particularly good, vulnerable and piercing. Though he has impressed enough, however sporadically (Punch Drunk Love, The Meyerowitz Stories, Uncut Gems, Hustle) that I can no longer register surprise.