I recently devoured Quentin Tarantino‘s Cinema Speculations, wherein he recounts his childhood and the succession of films his mother’s boyfriends would take him to see when he was a kid. Most of the films he discusses are ones you probably shouldn’t take a kid to see.

When my mother and father got divorced, I was six years old and my father was supposed to take us every other weekend for two nights. That arrangement became a little less frequent over the years, and by later grade school, he was taking me and my brother on a Saturday day and an overnight. We would spend the weekend with him at his apartment and pretty much do the same thing every time: go shopping, do his errands, look for stereo equipment, maybe spend an hour or two at his law office, go Putt Putt golfing, and then to Shakey’s Pizza in Rockville or The Charcoal Grille in Bethesda. Dinner was from Swanson’s, so you got a entree’, two sides, and a dessert.

And movies. We went out to the movies a lot. Or, we stayed in Dad’s apartment, where he had a special key that was hooked up to some kind of internal cable system, and we could watch close to first-run movies there instead of going out. Or just catch what was on TV.

My father loved movies, he loved to talk about movies, he lived for movies. So much so that he would go through a certain kabuki with me where he would let me take a look at The Washington Post and ask what I wanted to see. I would pick a Herbie the Love Bug and he would say, “Nah. I heard about this good movie.” And then, like Quentin Tarantino with his mother’s boyfriends, you went to see a lot of dark, heavy, violent flicks, like The Laughing Policeman, The Silent Partner, Death Wish, or The Taking of of Pelham One Two Three. Or the remake of Farewell My Lovely, Night Moves, or The Eiger Sanction.

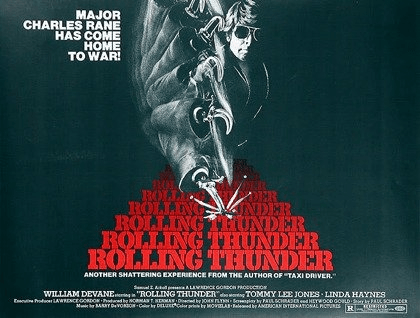

And Rolling Thunder. Which I noticed was available, and, as I couldn’t sleep anyway, I watched last night

Tarantino’s book has an entire chapter on the film, one of Paul Schrader’s first screenplays after Taxi Driver. Major Charlie Rane (William Devane) and Sergeant Johnny Vohden (Tommy Lee Jones) return to Texas after seven years of brutal captivity in a North Vietnamese prison camp. The adjustment is fraught, and even greater tortures are brought to bear on Devane, who is being treated by an Air Force psychiatrist (the just recently deceased Dabney Coleman) in his attempt to readjust. Tragedy ensues. Devane snaps. What follows is a classic 70s revenge flick.

The film travels wonderfully. There is a crisp foreboding to Devane’s return. While San Antonio welcomes him with marching bands and celebrations, and he is reunited with his long suffering and loving wife and the son who he last saw as a baby, Devane is damaged, and beneath the cheery gleam of a welcoming Texas, there is rot and danger. His son has anxiety issues. His wife has found another man (Devane says to her evenly, “you’re not wearing a brassiere” to which she replies, “oh, no one wears them anymore”). He cannot sleep in the house, preferring a cot in the garage.

So much is done well in the lead-up to the Death Wish-ian payoff, it goes unnoticed because, after all, this is a shoot ’em up, just desserts pic. Per Tarantino: ““This opening thirty minutes is a grippingly detailed character study, and by the time it’s over the audience doesn’t just sympathize with Charlie Rane, we really do understand him. Apparently better than anybody else in the film. It’s a much deeper depiction of the casualties of war than the [other movies of that era].”

I remember watching the film with my father. It is engrossing, both subtle and visceral, like a lot of pictures we saw together. It is also wildly inappropriate, also like a lot of pictures we saw together. I had trouble wrapping my head around something horrible that happens to Devane; not a spinning, vomiting Linda Blair kind of visual, but a brutality so smartly connected to a mundane part of the household, it just traveled with me, and probably not in a good way. Even last night, I fast-forwarded.

But on Sundays, when we were dropped off, I would not tell my mother about any of these movies, because I felt me and my Dad had this thing, this bond, and it was cemented in our little secret, Jujufruits and Junior Mints in hand. And perhaps we did, although I’m probably mythologizing it. After all, my father needed to have something to talk to me about. Or at a minimum, just a two hour break from my babbling.

The picture is currently on Amazon Prime. Nostalgic for me but it really holds up.