There are figures who defy biography. Some are dolts who we lionize because of an electric public persona, but after we peel back the skin, dig in, and nothing but soft goo is revealed, we adorn them with meaning if only to combat the dullness and our disappointment. Some are opaque, having lived a purposefully secretive life that does not lend itself to exposition. Some are so mythic, hagiography follows, lest a god be sullied. And many are just boring through and through, even if their impact was monumental.

How best to approach Donald Trump? I was thinking about why Saturday Night Live has such a problem caricaturing Trump and concluded that it is difficult to lampoon a cartoon. Trump is thuggish, brash, bombastic, ridiculous, and his persona – both before and during his political career – is that of someone who is already playing a part, man as product. Someone once observed that Bill Clinton was the most authentic phony they’d ever encountered, which makes him Trumpian on one level. The persona so effectively swallows the person that the former becomes innate.

Now, I don’t know what Donald Trump (or Bill Clinton, for that matter) is like privately, and Hollywood has yet to take on Clinton in biopic (we’ve had snippets, most recently Ryan Murphy’s rendition of the Lewinsky scandal, but nothing penetrating or overarching). And neither does screenwriter Gabriel Sherman. But he takes a fair stab, and it’s a game effort, for a time.

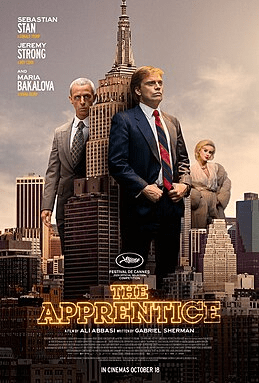

We meet Trump (Sebastian Stan) in the 70s, an ambitious son of an old-fashioned real estate developer who strives for entrée’ into tony Manhattan clubs while working for Daddy, collecting his rents in cheap New Jersey apartment housing. Donald has a dream – to develop a hotel in the then-hellscape of 42nd Street – something his father (Martin Donovan) considers an ill-advised fantasy. But Trump persists and soon, he meets another father figure, Roy Cohn (Jeremy Strong), who becomes his tutor and mentor. Cohn, a sybaritic fixer, protégé’ of Joe McCarthy, and executioner of the Rosenbergs, blackmails those who attempt to thwart his new charge, facilitating Trump’s rise. We watch Trump ascend, while negotiating the death of his alcoholic brother, eclipsing his father, and falling in love with Ivana (Maria Bakalova), all the while with Cohn in his ear. This is the part of the film that works, as we see a progression, both maturation and degeneration.

When we hit the 80s, Trump is on top, Cohn is crippled by AIDS, and their relationship deteriorates. With what feels like the snap of a finger, Trump is callous and brutal, as he repeats the Cohn mantra (attack, deny, always claim victory). But we don’t really see him ever employ those rules. In fact, he just reappears as a brute, and we are treated to the litany of rumor, concoction or well-known unflattering fact without context or explanation. Trump abandoned his brother, raped and verbally abused Ivana, tried to take financial advantage of his doddering father, gave Cohn fake diamond cufflinks, swung and missed in Atlantic City, took a lot of speed, wrote The Art of the Deal, mused about a political future, got liposuction and a scalp reduction, and is a germaphobe. One box after the other perfunctorily ticked. Just overt capsules, with all character-development jettisoned for dizzying visuals of the corrosive jet set life.

I suppose Sherman was trying to portray the seduction of Trump in concert with the go-go 80s, but it was done much better by Oliver Stone with Bud Fox in Wall Street, and even that movie can be garish and obvious.

What does work, however, works very well. The Trump-Cohn relationship is beautifully drawn. The elder sees talent and vitality in the son he never had and a young man he refrains from seducing sexually, while the understudy finds the father who truly believes in him. When the former imparts his wisdom, it would have been nice if Sherman could have employed it more directly as the basis for Trump’s rejection, but it is enough that the devil gets his comeuppance from his Frankenstein, and you know it works, because you kind of feel bad for the devil.

Stan and Strong are riveting and I expect both actors to be nominated. Even if they were undeserving, Trump is irresistible bait for the Oscars and given the unflattering vignettes of the film and the fertile environment for decrying the Bad Orange Man, we and the Academy shall not be denied.

Luckily, the actors are deserving. Strong is quickly becoming one of the most innovative character actors of his generation (I cannot so on enough about his turn in last years’ Armageddon Time, which, ironically, also included a young Trump character), and Stan manages to humanize a cartoon while incorporating the now ubiquitous Trump cadence and physicality, but doing so in a way that shows the features in infancy, so we can envision what they will be when we turn on our TVs today. Per Sherman, “And I think what Sebastian did so brilliantly is that he doesn’t try to impersonate Trump. He finds his own version of the character. And it works in a way where you feel like you’re watching a real person. You’re not watching Sebastian trying to be Donald Trump.” Dead on.

A solid, game, entertaining, very flawed near-hit that peters out.

On demand.