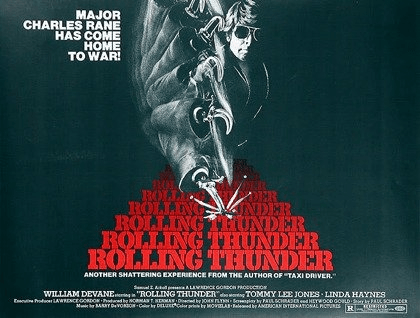

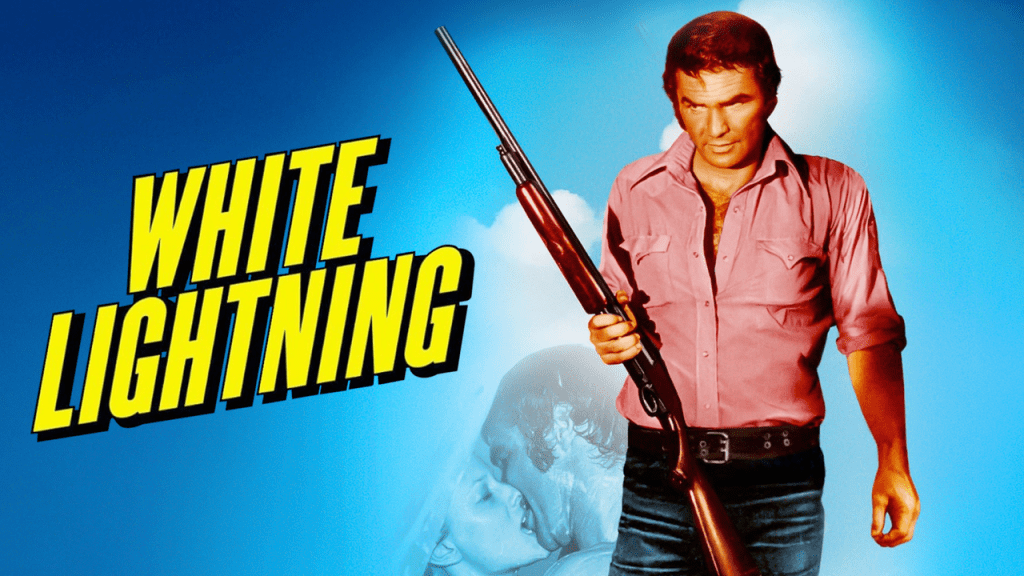

I was abandoned this past weekend, and I don’t do well alone. With an empty house and the care of a disinterested 15-year-old cat entrusted to me, I took the time to catch up on a few 70s flicks in my queue, including this strange creature.

Burt Reynolds – not at the height of his popularity, but post-Deliverance – is Arkansas inmate Gator McCluskey. He’s in the federal pen for illegal liquor running when he learns that a crooked sheriff (Ned Beatty) has murdered his younger brother. Why? Because the brother was a meddlesome hippie, and Beatty does not like hippies. So, Gator gets out, insinuates himself into the county, and exacts his revenge.

There’s a lot bad to meh here. The “I hate hippies” thing is unexplained – we never really know what the kid did to deserve being dumped in the swamp, and a sit-down between Beatty and Reynolds never happens. And the women of the Arkansas county are so carnal in their attraction to Gator, it seems cartoonish. Worse, there are tons of car chases, but not of the ilk of The French Connection or The Seven-Ups or Bullitt. Just a lot of banal vrooming around dusty country roads. From this demon seed sprouted Smokey & the Bandit and Cannonball Run (Hal Needham was a mere stuntman for the picture, but a few years later, he was second unit director on a reprise, Gator, and then he moved on to directing the slop that was Smokey and the Bandit I & II and Cannonball Run I & II). The first glimpses of Reynolds’ giggling, slapsticky, “I don’t give a fuck” mien can be found in the flick as well.

There are a few notes on the plus side of the ledger. Reynolds connects. He has movie star gravitas and just enough menace left over from Deliverance to project power and fear. Beatty is also strong, exuding a meanness and lethality in the guise of a portly bureaucrat. The film also takes a few runs at a healthy cynicism.

Fun facts – at the tail end of his career, the picture’s screenwriter, William Norton, did 19 months for ferrying guns to the IRA. After being released from prison, he moved to Nicaragua, where he shot and killed an intruder in his home. He then spent a year living in Cuba, was unimpressed, and was smuggled into the U.S. by his ex-wife.

Where is this film?

On Amazon, not recommended except as a curio.