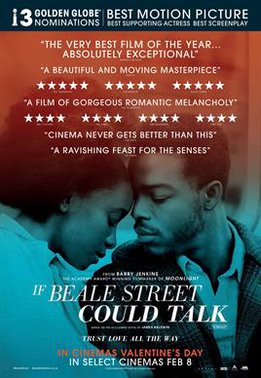

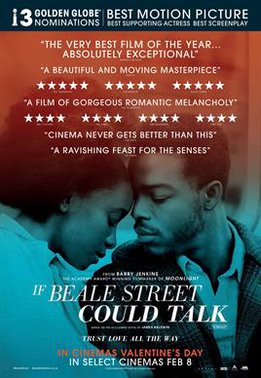

Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight was the best film of 2016, and his latest picture is of the same high quality, with the same dreamy, contemplative finish. Told in flashback and forward, Jenkins’ script is based on a James Baldwin novel set in 1970s Harlem. We meet childhood friends Tish (Kiki Layne) and Fonny (Stephan James) as young adults who have become lovers. Fonny is imprisoned for a crime he did not commit, and a pregnant Tish, with her family and Fonny’s father, work to pay the legal fees and perform the legwork to free Fonny from prison.

While this film is about many things, at its core, it is a love story, and Baldwin lovingly melds the city and the courtship with great care. There are scenes that seem almost like portraits, sensuous and evocative, such is the care he takes with his actors and the setting.

The film is also about race, and in this regard, it is subdued in its expression but forthright in its message. Baldwin is not interested in a political discussion, but instead, a demonstration of how racism pervades the lives of his characters in the seams, adding just another weight to an already heavy institutional burden. In the wrong hands, the theme would be overwritten and perhaps worse, overacted. Not here. The drag of the inequity is not sugarcoated but rather, presented as an open, inescapable legacy for the characters, which leaves a deep impression.

I have two criticisms. First, Tish often speaks in voice over, which I am not opposed to in all circumstances, but which also suggests a little distrust in the narrative. Given the ethereal nature of the picture, Jenkins likely felt it necessary to have Tish’s voice explicitly draw us back to the story, but I found it obtrusive and unnecessary. Second, a racist cop sends Fonny away, and when we meet him, he is so gruesome, so cartoonishly evil, it almost felt as if he would twirl his mustache. Perhaps that is what Jenkins was going for, to show the cop as the bogeyman the characters see, but I have to say, it was discordant.

Finally, all of the performance are impressive, but as Tish’s mother, Regina King is understated, yet commanding. She is a veteran of many movies (Ray, Enemy of the State) and even more TV series where she’s mostly powerful and overt, but here, she transcends anything she has done before with a subtle, restrained, nuanced performance.