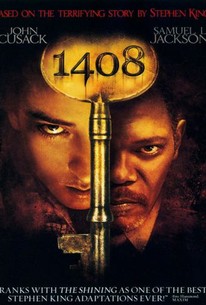

With Halloween nearing, and my son in eighth grade, the number of scary films appropriate for him to see is increasing, and he is chomping at the bit (he’s already secured a promise from me that I will take him to The Exorcist for its 40th anniversary next year). I remembered 1408 as having been both scary and appropriate and so we watched it this weekend. It is scary and appropriate, but on a second viewing, it is pretty weak tea,

The movie is based on a Stephen King short story, so naturally, the protagonist (John Cusack) is a writer, and not just any writer, but that certain writer whose first book was brilliant and serious and moving, but it just didn’t sell (how could “The Long Road Home” not sell?). Cusack is James Caan in Misery, even down to the sole cigarette. So now, embittered, Cusack writes a schlocky travelogue based on his visits to haunted hotels, inns and B&Bs. Cusack is enticed by an anonymous invitation to spend the night in New York City’s The Dolphin Hotel, room 1408. Despite the best efforts of its manager (Samuel L. Jackson) to dissuade him, Cusack insists, and soon, he is ensconced and psychologically assaulted.

The lead up is good stuff. Cusack is convincingly cynical in his pooh poohing and Jackson is effectively ominous in his warnings. Moreover, the plot is equipped with a nifty “in” to the room – Cusack’s agent (Tony Shalhoub) engaged lawyers to find a civl rights statute that prohibits a hotel from refusing to rent an available room.

But there are only so many holes that can be patched. Cusack learns that there have been 56 deaths, both natural and unnatural, in Room 1408, and Jackson also informs him that recently, a maid went in the room and gouged her own eyes out. Cusack doesn’t believe it, which is fine, but Jackson knows the room is a meat grinder. How in the world could the room be made available to anyone under any circumstances? The civil rights law wouldn’t override gutting the room, or making it a part of the hallway, or simply declaring it off limits to any renter. And who needs to tidy up this room?

This is a failure of writing. There are any number of ways around the “we have a haunted room but it is still available” conundrum, but first, you have to cut the body count down by 46 to make its availability to Cusack, even under threat of litigation, reasonable, and its availability to victims 15 and up plausible.

Once Cusack gets in the room, it becomes a decent fright fest, starting with a few slight tricks (chocolates on the pillow appearing magically, a creepy clock radio that only plays The Carpenters). Ghost jumpers follow, then an unexplained slasher and soon, you name it, it happens. The room plays on Cusack’s pain, and torments him, inevitably, with the memory of his dead daughter.

Cusack is excellent as a man fighting losing his mind, but without backstory, the movie becomes all about the visuals. And those remain interesting only for so long.

Still, state senator Clay Davis from The Wire (Isiah Whitlock, Jr.) steals the picture in his one scene as a reluctant air conditioning repairman. So there’s that.

Sheeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeit!