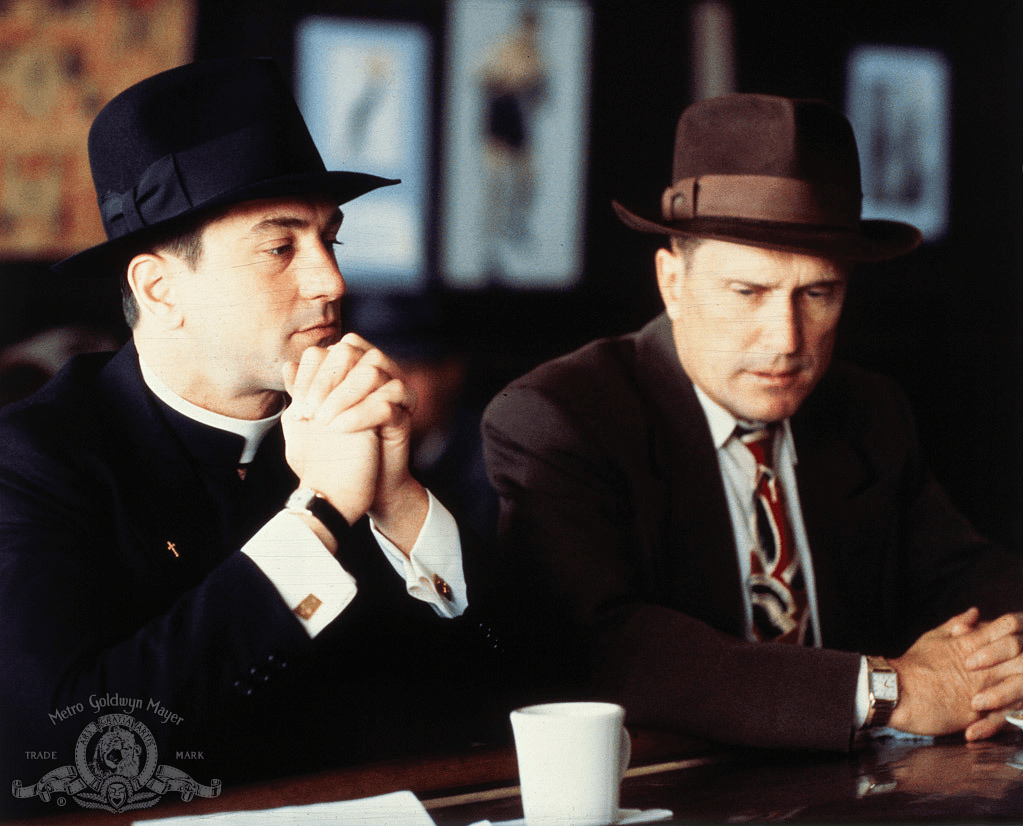

An unheralded gem, powered by the stellar performances of Robert De Niro and Robert Duvall, as brothers Dez and Tom Spellacy. De Niro is a rising monsignor in post-WWII Los Angeles, archbishopship on the horizon. Duvall is a tainted LA homicide cop. De Niro is ambitious and technocratically capable but fast becoming disillusioned with the moral elasticity necessary to keep the church afloat, including being chummy with the likes of a scumbag real estate mogul (Charles Durning, who seeks the church as beard for his corruption and literally sweats menace). Duvall is trying to make up for his past as a bagman. A Black Dahlia-esque murder connects them, and as De Niro wrestles with his faith and station, Duvall agonizes over his past crimes and his attempt to make amends by going after Durning, damage to his brother be damned. We learn about their secrets and upbringing in an L.A. that has a Chinatown-vibe.

One of my favorite fiction authors, John Gregory Dunne, wrote the screenplay with his wife Joan Didion, and it exudes verisimilitude and deftness. The script allows De Niro and Duvall significant space and what they do with the quiet moments is poignant. There is always tension, but also, always an intimacy and a shorthand that speaks to shared happier, or unhappier, times. Their exchange on their uber-Catholic mother is emblematic:

Tom Spellacy: How’s ma? Is she still eating with her fingers?

Des Spellacy: Well, she says the early Christian martyrs didn’t have spoons.

Tom Spellacy: Tell her they didn’t have Instant Cream of Wheat, either.

It’s a cheat to cite a review within a review, but Vincent Canby’s is so dead on and conclusive, I’ll transgress: the film is a “tough, marvelously well-acted screen version of John Gregory Dunne’s novel, adapted by him and Joan Didion and directed by Ulu Grosbard who, with this film, becomes a major American film maker. Quite simply it’s one of the most entertaining, most intelligent and most thoroughly satisfying commercial American films in a very long time.”

If there is a problem, it is third act, which could have used a few more moves to get to the ultimate revelation. But I’m hesitant even in that criticism for fear that any nod to beefing up the procedural would have taken away from Grosbard’s patience and care with the characters. The film not only showcases De Niro and Duvall, but takes time to establish real connections between De Niro and an older priest (Burgess Meredith), who De Niro puts out to pasture because of the latter’s interference and sermonizing (“I’m not a man of the cloth, I’m a man of the people”); Duvall and a whorehouse madame (Rose Gregorio) with whom he had some sort of ragged relationship until she took the fall for his crookedness and did a stint in jail (“I need you like I need another fuck,” she spits at him); and Duvall and his partner, Kenneth McMillan, who shakes down Chinese restaurants for his retirement motel and tries to keep Duvall out of trouble (“You know who we’re going to pull in on this one? Panty sniffers, weenie flashers, guys who fall in love with their shoes, guys who beat their hog on the number 43 bus. What? Do you think I’m gonna lose any sleep over who took this broad out?”). The blunt and cynical nature of the dialogue aside, Dunne and Didion never stoop to hackneyed tough guy patter, and they counterbalance with real tenderness. The train station scene where the parents of the murdered girl meet with Duvall to take their dead daughter home is one memorably piercing example.

Just added to Amazon.