Writer/director James Cameron’s blockbuster is lovingly grand and its atmospherics and visuals breathtaking. But a single scene exemplifies the failure of the picture.

The moment before the lookouts spot the iceberg that would seal their fates, they’re dicking around watching Rose (Kate Winslet) and Jack (Leonardo DiCaprio) smooching on the foredeck. As a result, a plausible argument can be made that the two leads sank both the ship as well as the film, because their insipid teen love affair is at the heart of this movie.

Rose is unhappily slotted for a marriage to a well-heeled snob (Billy Zane). She intends to fling herself off the ship, but she is saved by and falls for roustabout Jack. As the ship continues its doomed voyage, these two chuckleheads moon at each other, while blithely noticing things that are important:

Andrews leads the group back from the bridge along the boat deck.

ROSE

Mr. Andrews, I did the sum in my head, and with the number of lifeboats

times the capacity you mentioned… forgive me, but it seems that there are

not enough for everyone aboard.

ANDREWS

About half, actually. Rose, you miss nothing, do you? In fact, I put in

these new type davits, which can take an extra row of boats here.

(he gestures along the eck)

But it was thought… by some… that the deck would look too cluttered. So

I was overruled.

CAL

(slapping the side of a boat)

Waste of deck space as it is, on an unsinkable ship!

ANDREWS

Sleep soundly, young Rose. I have built you a good ship, strong and true.

She’s all the lifeboat you need.

Not enough lifeboats, you say?

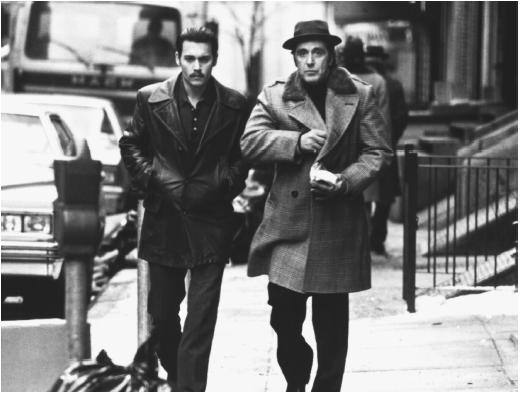

Soon, Rose is posing nude for Jack (he is a portraitist) and shortly thereafter, they’re going at it hot and heavy. Zane is infuriated and sets his goon (David Warner) on Jack, leading to an implausible cat-and-mouse chase through the ship while it is going under (Warner is truly Employee of the Century).

There are many, many other problems. DiCaprio could not be more wrong for the part. He looks as if he just started shaving, so his turn as a man-of-the-world is laughable. It’s an Aidan Quinn role given to a near pre-pubescent.

Rose, did you see where I put my Bubble Yum?

Cameron’s script is also unbearably overt. He trusts his audience not, as early exposition demonstrates:

HAROLD BRIDE, the 21 year old Junior Wireless Operator, hustles in and

skirts around Andrews’ tour group to hand a Marconigram to Captain Smith.

BRIDE

Another ice warning, sir. This one from the “Baltic”.

SMITH

Thank you, Sparks.

Smith glances at the message then nonchalantly puts it in his pocket. He

nods reassuringly to Rose and the group.

SMITH

Not to worry, it’s quite normal for this time of year. In fact, we’re

speeding up. I’ve just ordered the last boilers lit.

Andrews scowls slightly before motioning the group toward the door. They

exit just as SECOND OFFICER CHARLES HERBERT LIGHTOLLER comes out of the

chartroom, stopping next to First Officer Murdoch.

LIGHTOLLER

Did we ever find those binoculars for the lookouts?

FIRST OFFICER MURDOCH

Haven’t seen them since Southampton.

Iceberg, speeding up, and no binoculars? Uh oh.

The film unravels at the end. The idiocy of Warner hunting Jack and Rose as the ship nears its final peril can no longer be ignored. Meanwhile, Cameron becomes enamored of what he can do on his broad canvas. Tragedy becomes an action caper as the director starts bouncing hapless victims off of fantails.

In the final scene, an aged Rose (Gloria Fisher) looks longingly into the icy waters that took her Jack, and throws a massive jewel in. Leaving your last thought as, “That damned thing could have fed Sub-Saharan Africa for a few months. What a selfish old hag!”