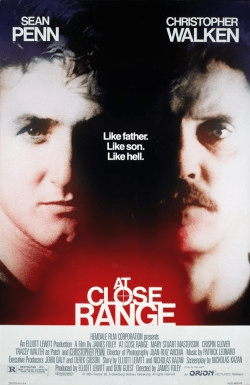

James Foley’s (After Dark, My Sweet) film never really decides what it wants to be, a family drama or a crime picture. Foley eventually throws up his hands and cedes everything to the captivating Christopher Walken.

Not the worst of decisions. Walken plays a minor rural Pennsylvania crime kingpin. He skippers a crew that includes his two brothers and a few other hardened locals. They do heists, car thefts, drugs, and, if necessary, murder, a lethal but merry band of crooks.

Walken’s estranged son, Sean Penn, is a townie still living at home with his mother and grandmother. The women smoke, glare at the TV and otherwise exude the hopelessness of abandonment and near poverty. Penn, seeking something more, falls in at-first-sight love with Mary Stuart Masterson, who looks his way as he cruises at night around the town square. It is for her that he joins up with his father’s crew, to “get out while we’re young … ’cause tramps like us …”

When Penn realizes murder is part of the gig, he splits from Walken, gets arrested working his own “baby” crew (which includes his brother Chris and a very young Crispin Glover and Kiefer Sutherland), and is incarcerated. There, the cops work on him to fink on his father.

Here, the film becomes ridiculous. Walken, paranoid Penn will flip on him, kills nearly every one of the kids working with Penn, even though Foley does not show them to be integral enough to his operation to be much of a threat. He also rapes Stuart Masterson, which makes even less sense if the plan is to bring Penn back into the fold. Penn comes out of jail, tries to make a run for it with his gal, fails, and in a rushed, abrupt ending, testifies against his father (for 30 seconds).

That’s that. Lights up.

None of it makes much sense, but the thematic indecision is worsened by gross character underdevelopment. Walken is a charming sociopath, but how did he get here? No clue. We even have his ex-wife moping about, warily eying the establishment of a relationship between Walken and Penn. Foley, however, suffices to use her as a sad totem, so we don’t get any insight into Walken from her. Similarly, Penn needs a Daddy. Then, on a dime, he doesn’t. As he is near mute for most of the picture, we are left to guess as to what he has missed and the basis for his immediate and strong moral stand. Stuart Masterson is looking for something, but as she and Penn prepare to light out for the territories, leaving her house, she is clearly from money. So why is she hanging with these lowlifes? Unexplored.

The film has its strengths. Foley’s feel for rural Pennsylvania is strong. The fields and woods are spooky and forbidding at night. During the day, the crappy cars and houses, the dead-end bars, they all contribute to Penn’s lust for some way to get out. Foley shows just how big and cold this country can be, the kind of place that swallows you up and tells no tales or grinds you down little by little. The murder spree is indelible.

As noted, Walken is the picture, and in every scene, he is riveting. Penn, however, goes low to Walken’s high, and the effect is somnambulant. He’s in with Daddy, then immediately out, then annoyingly internal until his final nose-to-nose with Daddy, all to the conclusion that he needed a better Daddy.

The story is apparently based on a true criminal, Bruce Johnston Sr.

Another note – at the time of the picture, Penn was married to Madonna. She had a song for the picture which then became extended to the soundtrack. It is synthy, mid-80s fare, better suited to Vision Quest or even Risky Business. It has no business being near this gritty movie. Sure, I joked about Springsteen above, but his music would have been pitch perfect to the film.

On Amazon Prime.