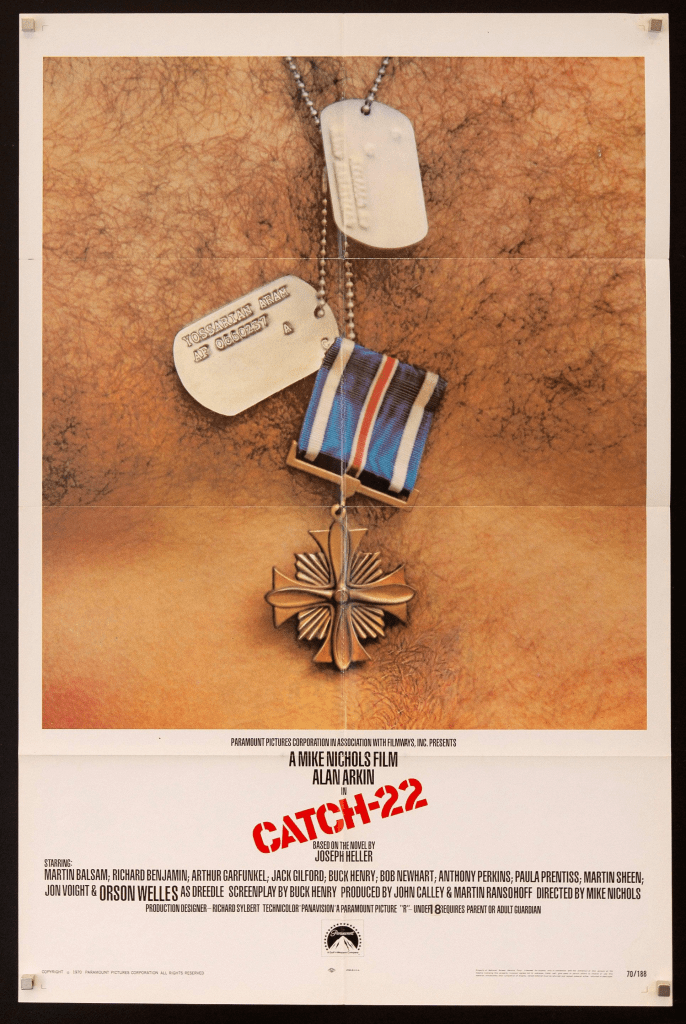

Mike Nichols’ adaptation of Joseph Heller’s dark comic novel is energetically brisk and sometimes entertaining. Tonally, however, the film is an uneven mess, a pointless downer playing bleakness for laughs.

As the original Corporal Klinger, Alan Arkin’s Captain Yossarian is the engine of the picture, a bombardier stationed in Italy who is losing his nerve and wits. His superiors (Bob Newhart, Buck Henry, and Martin Balsam) vex him by upping the number of bombing missions necessary for a ticket home to curry favor with their commanding officer (Orson Welles). Yossarian’s fellow fliers (including Martin Sheen, Richard Benjamin, Anthony Perkins, Charles Grodin, Bob Balaban, Jon Voight, Art Garfunkel, Jack Gilford and Norman Fell ) all suffer under the same yoke, but with cheerful acceptance or apathy rather than the indignation of Arkin’s whirling dervish. How the Academy overlooked Arkin astonishes me; whatever the flaws of the picture, his commitment and on-the-edge turn requiring an actor’s entire skill set is unforgettable.

The film’s main problem is rooted in the see-sawing expanse of the endeavor. Yes, war is FUBAR, and aspects of it are both craven and bizarre. In the world of Nichols and Heller, the poor bombers are riddled with asinine and unctuous leadership, wackadoodle stir-crazy types, suicidal loons, sex-crazed fiends, one murderer, and one uber-capitalist who trades parachutes for commodities on the open market.

When played for laughs, the picture is solid, and no one is begging for verisimilitude. However, when pathos is introduced, such as truly tragic deaths of compatriots (including a particularly brutal death of a young flier) and civilians, the film feels incongruously cruel.

Worse, the picture is more than anti-war. It is anti-American, maybe even anti-everything. As nothing matters, there is no investment in the fates of anyone. A fair juxtaposition is Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H, in which the madness of the endeavor is clear but even in that madness, the professionalism of the medical staff is unquestioned and laudable, the loss of life truly sad. Nichols himself felt M*A*S*H did his picture in: “We were waylaid by MASH, which was fresher and more alive, improvisational, and funnier than Catch-22. It just cut us off at the knees.” All of which is true. But M*A*S*H also had heart and a respect for the craft of combat surgery. Here, there is no respect for anything or anyone and the characters seem more from Looney Tunes than Heller’s book.

Indeed, every hallmark of the American ethos is there for Nichols to malign. The military leaders are insecure dolts, silly and moronic, who care not a whit for the men. The fliers are chumps or burn outs, pawns in the great game, either oblivious or devious in their plans to get out and shirk. Everyone is also an automaton, caring for nothing, even each other. The goal and aim of the war, and this is World War II we are talking about, is at best corrupt and ultimately criminal, as we bomb not only towns with no military significance, but, in a perversion of capitalism, we allow the Germans to bomb our own base for profit. The Italians are victims of the Americans, just as they were victims of the Germans, because, you see, there is no difference between the two. By the end of the picture, the genius behind the corporate conglomerate, Jon Voight, is now close to full Nazi in regalia and trappings.

Hell, even parents who come to Italy to see their dying son are treated as props for a goof.

Yes, yes. None of this is to be taken literally in a “war is madness” story, and the film is a black comedy grossly overgeneralizing for the laughs. Still, it’s the kind of smart set entertainment that fairly encapsulates the philosophy of the sophisticate, a sneering besmirchment that puts the last torpedo into a sinking ship.

I wonder what Heller made of the movie’s iciness. Obviously, his book was a cynical send-up (I read it in high school, along with Vonnegut’s SlaughterHouse-Five), but Heller also flew 60 combat missions as a B-25 bombardier during the war.

On Amazon Prime.